git exercise

If you're working on a file, you might be in the habit of saving versions every so often. If your file's called project you may create project2, project_old or projectJuly31 before making some changes, in case you change your mind. That's all well and good, but your folder gets cluttered, and if you have lots of files, or create alternative versions or if you're part of a team, that way of working becomes very messy.

In this kind of situation,

In this kind of situation, git is especially useful.

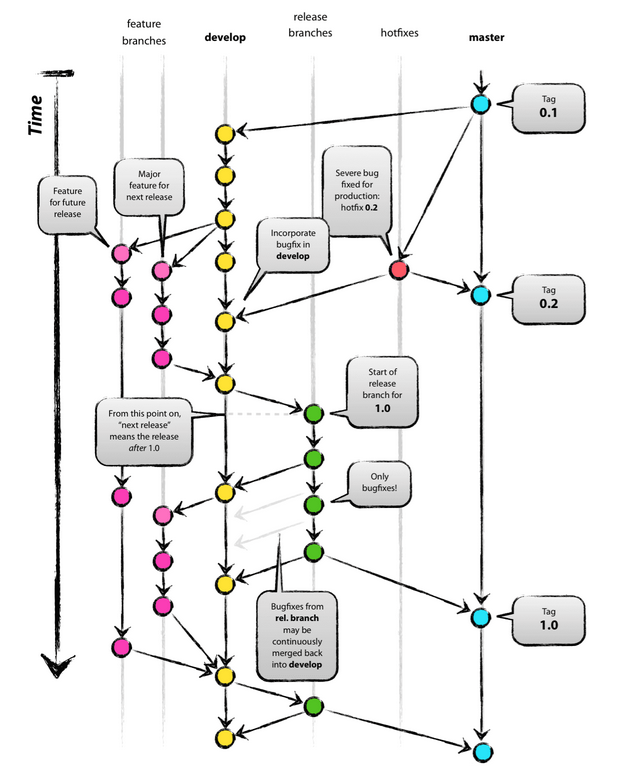

git is a revision control system that helps you manage modifications to your work. It lets you backtrack if things go wrong, and in team projects it helps coordinate modifications. It's free, and can be used across the Web. Even so, because it's designed to cope with complex situations like the one on the right (it was designed to deal with the Linux source code) it can seem like overkill in simpler situations. And you can get yourself in a tangle. Don't panic - there's always a way out.

This exercise is written primarily for Unix users working from the command line, so here's a crib sheet of Unix commands.

ls- list files in the current foldermkdir folder_name- make a new folder (unix calls folders directories)cd folder_name- go to the named folderpwd- find out which folder you're inmore file_name- display the contents of file_name on the screenecho text > file_name- put the text into the file, overwriting what was there, creating the file if necessaryecho text >> file_name- append the text to the file[up arrow]- retrieve the previous line. You can use this repeatedly, and edit the retrieved line. Wherever the cursor is, pressing the Enter key will run the whole line

The online version of this document is at http://www-h.eng.cam.ac.uk/help/unix/git/exercise.html. More information is available from http://www-h.eng.cam.ac.uk/help/unix/git.

Setting Up

The git commands store the updater's name and can sometimes start editors. Running the following commands will stop git warning you that you've not configured your set-up. You can do the first worked example below without any of these being correct (you won't need an editor, and all the files are temporary). On Linux you could set the editor to be emacs.

git config --global user.name "Your Name" git config --global user.email YourEmailAddress git config --global core.editor YourEditor

A worked example - one user, one repository

Here I add a line to a file each time using the echo command, but you could edit the file instead

- Create an empty folder and create a repository (a place to store git's files)

mkdir /tmp/gittest1 cd /tmp/gittest1 git init

- Create a file called

one, tellgitthat you want to keep track of it, then store the current version of it and give the version a name. If thecommitcommand warns about your configuration, try the Setting Up commands.echo first line > one git add one git commit -m "a one liner" git tag -a -m "base level" base

Thegit addcommand adds the named file to the list of files thatgit commitwill save. You don't have to add a tag, but as you'll see later, it makes jumping between versions easier. - Add another line to the file and save a version. Note that this time the

commitcommand has a "-a" flag, meaning that it will save all the files (i.e. we don't need use "add" to specify which files to save). Then do it again.echo second line >> one git commit -a -m "a two liner" echo third line >> one git commit -a -m "a three liner"

If you type more one you'll see that your "one" file will now contain

first line second line third line

Now you can view the structure of the current project using

git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

which displays something like this (your numbers will be different)

* 0ad5dd6 (HEAD, master) a three liner * 265211c a two liner * 66b374a (tag: base) a one liner

Each of these lines denotes a stage that you can go back to. To return to the start, type

git checkout base

(don't worry about the long note that git displays) or use the numerical name - in this case 66b374a

git checkout 66b374a

If you look at the "one" file now using more one, you'll see your original version

first line

If you type

git checkout master more one

you'll see your newest version again. For a small, single user project, this may be all you need to know about git. If you type

git commit -m "a comment"

every so often during your project you'll build up a sequence of back-up versions of your work without cluttering your folder. At any time you can do

git log- to get a list of dates when you committed things, and what you committed.git diff ...- to compare versions. For example,git diff base master

will show the differences between your first and final versions (in a format that you'll soon get used to).

Your folder won't be cluttered - everything's in the .git folder. If you set up a remote repository and do git push after each commit, you'll have a remote backup of your work. Better safe than sorry.

Branches

This project has developed linearly so far. Let's suppose you're already having second thoughts about how you project's developing. Typing

git checkout base git checkout -b bough

goes back to the start and gets ready to produce a branch called "bough". Doing

echo a new idea >> one git add one git commit -m "along the branch" git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

produces something like

* 3246626 (HEAD, bough) along the branch | * 0ad5dd6 (master) a three liner | * 265211c a two liner |/ * 66b374a (tag: base) a one liner

showing that now there are 2 tracks of development from base- the current one (shown as a vertical line leading to "bough") and the one we first produced (the "master").

To create a new branch named "experimental1" without checking it out, use

$ git branch experimental1

If you now run

git branch

you’ll get a list of all existing branches:

* bough experimental1 master

The "experimental1" branch is the one you have just created, and the "master" branch is a default branch that was created for you automatically. The asterisk marks the branch you are currently on. Type

git checkout experimental1

to switch to the experimental1 branch. We'll add text to the file, and commit the change:

echo an experiment >> one git commit -a -m "my first experiment"

Add another branch now, and switch back to the master branch

git checkout bough git branch experimental2 git checkout experimental2 echo another experiment >> one git commit -a -m "my second experiment" git checkout master

If you look at the "one" file now (e.g. by typing more one) you'll see the three line version - because you’re back on the master branch. You can make a further change on the master branch. Let's add something

echo fourth line >> one git commit -a -m "a four liner"

By now the branches have diverged, with different changes made in each. Typing

git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

will produce something like this -

* 7ad13d3 (HEAD, master) a four liner * 97f7ec4 a three liner * 999886f a two liner | * ad63635 (experimental2) my second experiment | | * 7e4e446 (experimental1) my first experiment | |/ | * a60312d (bough) along the branch |/ * f5b2477 (tag: base) a one liner

Already you have 3 streams of development on the go, and different versions of each. This is typical when writing a program (or a poem come to that). Suppose now that you thought experimental1 was a good idea. To try merging the changes into the master sequence, run

git merge experimental1

If the changes don’t conflict, the merge will be done automatically. If, as here, the two strands of development conflict, you'll get a message something like

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Markers will be left in the problematic files showing the conflict. If you do more one you'll see that it's been changed -

first line <<<<<<< HEAD second line third line fourth line ======= a new idea an experiment >>>>>>> experimental1

This shows you that the 2 versions have a line in common but then differ - above the "=======" line is the master version, and below is the experimental1 version. Typing

git diff

will also show the differences. You will need to edit the one file to merge the 2 version manually. You could for example make the contents of one be

first line second line third line a new idea an experiment

You can then type

git commit -a -m "merged version"

to commit the result of the merge. At this point you could delete the experimental branch with

$ git branch -d experimental1

Typing

git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

now displays something like

* 6f804c4 (HEAD, master) merged version |\ | * f7da77f my first experiment * | b52fa9c a four liner * | 0ad5dd6 a three liner * | 265211c a two liner | | * d8931e0 (experimental2) my second experiment | |/ | * 3246626 (bough) along the branch |/ * 66b374a (tag: base) a one liner

showing the merge and the abandoned

showing the merge and the abandoned experimental2 branch. If you type

git diff master experimental2

You'll get

diff --git a/one b/one index ffea0ad..1436297 100644 --- a/one +++ b/one @@ -1,5 +1,3 @@ first line -second line -third line a new idea -an experiment +another experiment

showing which lines the 2 versions have in common ("first line" and "a new idea") and which lines are in one version but not the other (denoted by the - and + symbols). Some versions of git show the differences in a friendlier way, colour coding the changes. Also they show the versions and branches in a friendlier way (see right).

detached HEAD

Normally the HEAD variable stores the name of a branch-end. However, git also allows you to check out an arbitrary commit that isn’t necessarily the tip of any particular branch. In this case HEAD is said to be "detached". If you continue the above example by doing

Normally the HEAD variable stores the name of a branch-end. However, git also allows you to check out an arbitrary commit that isn’t necessarily the tip of any particular branch. In this case HEAD is said to be "detached". If you continue the above example by doing

git checkout base

you'll be told "You are in 'detached HEAD' state". It's important to know that you're in that state because if you make changes to files and commit them, they'll disappear the next time you do a checkout, so beware.

Names

Descriptive text ("tags")can be added to nodes. There are 2 types of tags. Annotated tags are meant for release while lightweight tags are meant for private or temporary object labels. For this reason, some git commands for naming objects (like git describe) will ignore lightweight tags by default.

See Also

Our git page has more worked examples. Also there's

- GPRS tutorial - an 83 page PDF document with many worked examples

- gittutorial - A tutorial introduction to Git - has a useful section on "Using Git for collaboration"

- gitworkflows - An overview of recommended workflows with Git

- Version Control with Git

- Tutorials

- git-guide

- a simulator

- A book (500+ pages)

Some of these quickly become detailed. A git cheat sheet might be useful.

- © Cambridge University, Engineering Department, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1PZ, UK (map)

Tel: +44 1223 332600, Fax: +44 1223 332662

Privacy policy

Contact: helpdesk